Using ATP Bioluminescence to Support Clinical In-Use Hold Times

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) Bioluminescence detection is an established technique for determining the presence of microorganisms in pharmaceutical, consumer health, and food products.

The application of this technique within the pharmaceutical industry has largely been for sterility and in-process control testing. Nonetheless, the use of ATP Bioluminescence is a proven technique to monitor microbial viability.

The Luciferase enzyme converts luciferin into oxyluciferin, producing light in the presence of ATP. ATP is present in all living cells and must be present for the reaction to occur; therefore, it can be used as a microbial testing marker for contamination if a sample should not (under normal conditions) contain ATP. ATP is the transport molecule for most cell metabolic processes (including replication and motility).

The assay is an amplified version of ATP bioluminescence; ATP drives the reaction that produces light, which is measured by a luminometer.

Definitive detection is based on having a sufficient quantity of microbial ATP present to generate a clear, detectable light signal. It uses an enzyme-catalysed reaction to overcome this limitation, reducing the time to result.

The amplification catalyses the production of additional ATP; the total amount of ATP can then be readily detected and measured using ATP bioluminescence. The ability of enzymes to catalyze reactions without being depleted or altered allows the generation of large amounts of their products. The reaction is essentially linear; the longer the reaction is allowed to proceed, the more ATP is generated. This strengthens the bioluminescent signal. After 25 minutes, the amount of ATP can be 1000 times more than was originally present.

The technique has been assessed, and within AstraZeneca, its validation for the sterility testing application has been completed. Method equivalency was demonstrated in accordance with the criteria outlined in the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <1223> Validation of Alternative Microbiological Methods and PDA Technical Report No. 33 (Revised 2013): Evaluation, Validation, and Implementation of Alternative Rapid Microbiological Methods. Further primary and secondary verification studies were conducted to further confirm the equivalency. The method was then subjected to a range of challenges during subsequent method verification studies, including assessing the variability of nutrient media from different suppliers and within batches from a single supplier. A wide range of organisms was covered, as well as “time-to-result” studies, which confirmed the detection of Propionibacterium acnes within 24 hours of inoculation and mould species within 72 hours of inoculation. The extensive studies performed within the laboratory were further complemented by studies performed at a subsequent site, and the reliability of the methodology was confirmed.

In conclusion to these extensive studies, the ATP Bioluminescence Technique provided a reliable and accurate way to monitor product stability.

For many parenterally administered drug products, material undergoes some manipulation in the clinical setting prior to administration, for example, addition to an infusion bag, or reconstitution of a freeze-dried material with a diluent. Whilst good aseptic practice is a measure of control in the clinical setting, it should also be considered that once the container is breached, there is a risk of microbial contamination. It is critical that the provider of the medicinal product understands any risks associated with microbial proliferation during the in-use period and mitigates these risks in the handling instructions.

During early phases of development, or in absence of product specific data, a typical hold time is often defined as “24 hours at 2-8°C, of which not more than 4 hours at Room Temperature” (1). However, during late phase development, or in circumstances where those conditions are not possible (for example chemical instability, remote sample preparation) microbial challenge studies are conducted to understand the risks and enable an appropriate in-use shelf life to be defined.

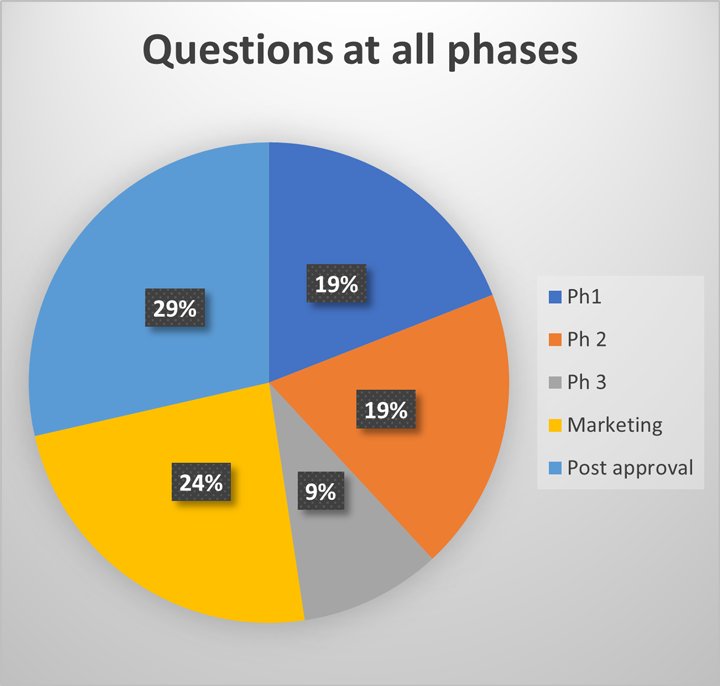

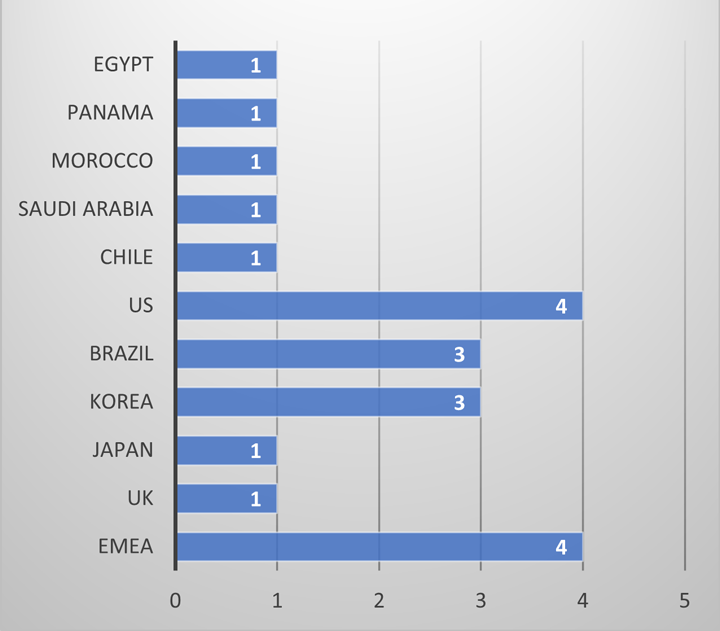

During both clinical trial and marketing applications, regulatory agencies request additional information to support the in-use hold time of a product within the clinical administration environment. A review of regulatory questions at AstraZeneca over the past four years demonstrates that these questions come from regulators all around the world, at all phases throughout a product life cycle (see Figures 1 and 2).

This is not only a regulatory concern but also a patient safety concern. Whilst compounding pharmacies and clinical pharmacies adopt good aseptic technique, the point of control is no longer with the manufacturer of the material. Therefore, it is prudent to understand if any additional risks should be mitigated during development.

Traditionally, challenge studies adopt the principles of USP <51> Antimicrobial Effectiveness and Ph Eur—5.1.3 Efficacy of Antimicrobial Preservation. There are inconsistencies over inoculum level, challenge organisms, and hold times applied when these studies are conducted. Furthermore, the definition of microbial proliferation can also be ambiguous with no clear guidance on what a safe cut off level should be defined as.

Samples of product are prepared in line with the clinical handling instructions (in some cases the volumes are scaled up or down); known levels of inoculum are then introduced to the samples, these will typically be the “compendial panel” of organisms; Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida albicans and Aspergillus brasiliensis. Inoculum levels remain below 1% of the volume of the sample. At predetermined timepoints, samples are aseptically extracted; as the levels of microorganisms present are not known, multiple dilutions are often prepared to enable accurate counts in Colony Forming Units (CFUs) following incubation. To ensure a range of data is collected, studies are often performed at multiple temperatures; therefore, multiple samples are plated out and assessed following a suitable incubation period. In some challenge studies, this may result in hundreds of plates being prepared, only to be found to have no growth recovered following the incubation period. Furthermore, the definition of microbial proliferation can be ambiguous, with no clear guidance on what a safe cutoff level should be.

As the ATP Bioluminescence technique is established within AstraZeneca, an experimental program was performed to assess the application of this technique for future challenge studies.

The study was performed on three “product” samples to represent best and worst cases:

- 0.9% saline

- 50:50 Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB):0.9% saline

- TSB

0.9% saline would represent a product with very low levels of nutrients available for microbial proliferation.

A 50:50 Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB): saline mixture was prepared to represent a worst-case product, as it would provide a more challenging environment than is typically observed for drug products, should a product supporting microbial proliferation be included in a clinical protocol.

TSB was selected as the most commonly used medium in the pharmaceutical microbiology laboratory because it supports the proliferation of a range of microorganisms. This would represent worst-case material, as the function of TSB is to culture microorganisms.

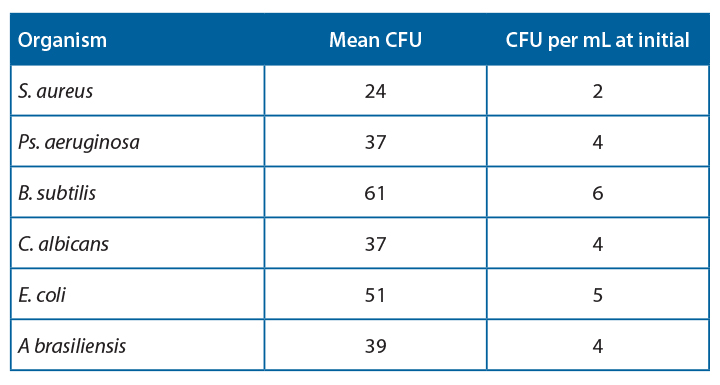

Samples were prepared and were inoculated with a target inoculum level <100CFU/100mL “product”. The organism panel included Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Candida albicans and Aspergillus brasiliensis. These were selected to represent the range of flora that may be observed during preparation: human skin commensal, common environmental isolate, waterborne organism, and environmental yeasts and moulds. The organisms also represent the range of microorganisms within the environment: Gram-positive cocci, Gram-positive spore-forming rods, and Gram-negative bacteria.

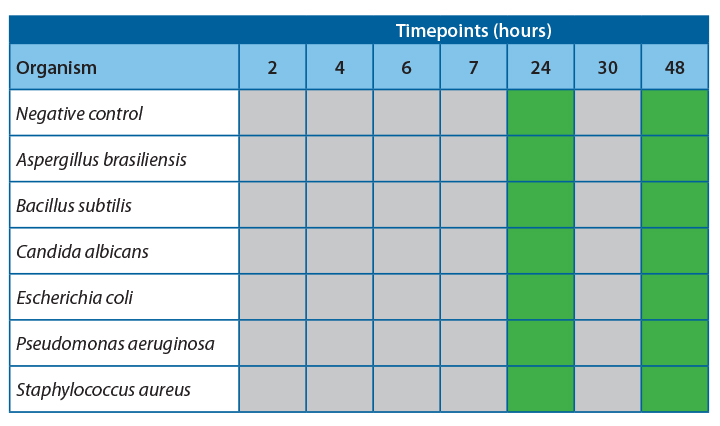

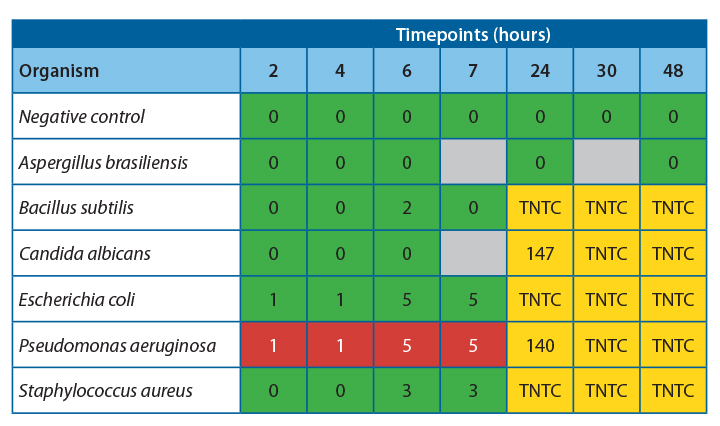

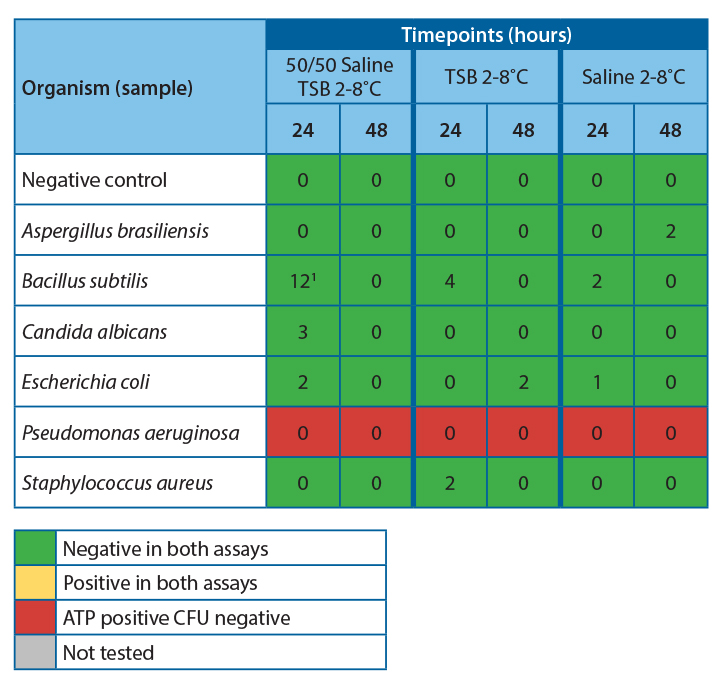

To support the “24 hours at 2-8°C, of which 4 hours at room temperature”, predetermined timepoints were established to take samples. Samples were tested using the ATP bioluminescence assay in parallel with traditional plate count samples.

Methods

Three sample types were prepared in duplicate: 100ml 0.9% saline infusion bags, 100ml 50/50 TSB Saline bags, and TSB bottles. These samples were inoculated with 1-10CFU/ml of Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphyloccus. aureus, Candida albicans, Aspergillus brasiliensis, and Escherichia coli.

The inoculated bags and bottles were then incubated at 2-8˚C and 20-25°C. Samples were tested at intervals over 48 hours using both ATP bioluminescence and traditional pour plate techniques.

The ATP bioluminescence assay was performed by testing 50µl aliquots in duplicate using the AMPiScreen assay to determine a qualitative positive or negative result.

To obtain a quantitative result for the number of colony-forming units, membrane filtration was performed by adding 1 mL of the sample to 100 mL of fluid A before filtration. Filtration plates were incubated at 30-30˚C for up to 5 days.

Results

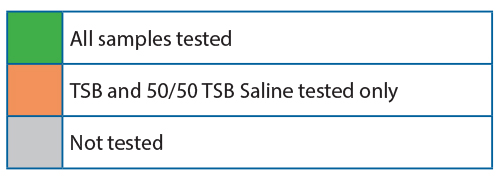

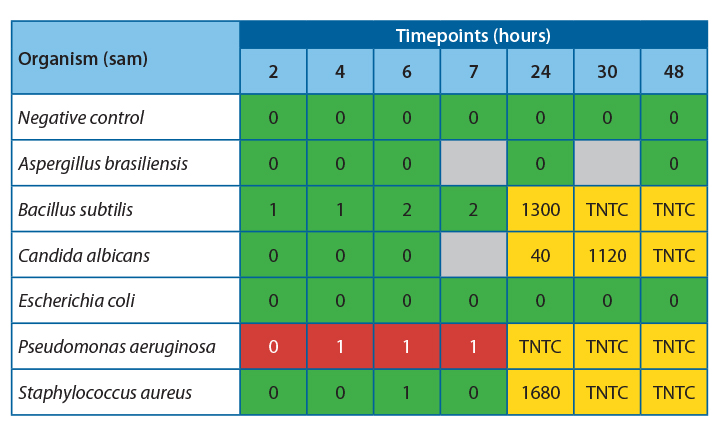

The Celsis assay is considered a qualitative test, with results reported as either positive or negative. In standard sterility test applications, the test article undergoes a culture and incubation period. In this situation, there has been no culture or incubation step of the test article. The samples were read directly in the instrument; therefore, the application here is as an indicator of viability.

For the traditional method, the log change has been calculated it is the risk of proliferation that is being tested for.

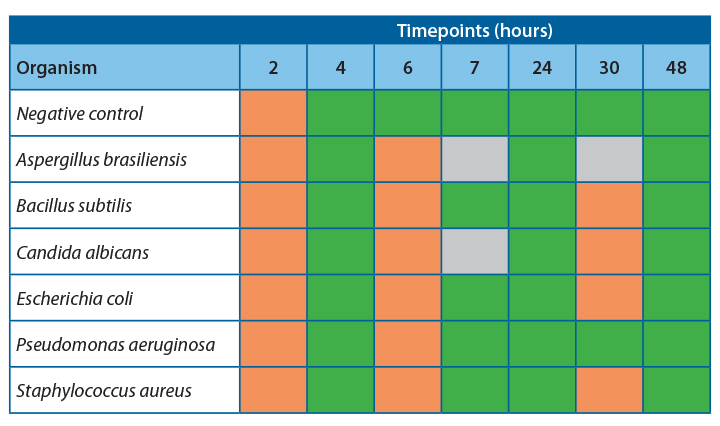

It was observed that there was 100% agreement between the two methods for all samples except Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Table 4 shows the agreeability of the two methods at each timepoint.

Conclusions and Discussion

For all samples, accept Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the filtration and ATP bioluminescence had 100% agreement. A positive ATP result was seen when a log 1 or more increase of growth was observed in the filtration method. Thus, indicating that this method would be suitable for detecting proliferation in challenge study samples.

Investigation into the high relative light units for Pseudomonas aeruginosa at low CFU levels has determined that this is due to extracellular ATP being present at high concentrations in this species. This increased the amount of light produced per cell, leading to a positive result throughout the experiment. If this technique were used for challenge studies, this would not be an issue, as any positive samples would be tested using the traditional filtration method to determine the count.

At 20-25˚C, no proliferation was seen until the 24-hour timepoint, indicating that proliferation occurred between 7 and 24 hours. To safely give a time at room temperature for more than 4-6 hours, more data would be required to determine the exact time at which growth becomes unacceptable in the untested interim period.

At 2-8˚C, no proliferation was observed over the 48 hours; this is a good indication that clinical products can be stored at this temperature for this time without concern for microbial proliferation.

References

- Metcalfe, J.W. (2009). Microbiological Quality of Drug Products after Penetration of the Container System for Dose Preparation Prior to Patient Administration.

Sophie Drinkwater is an associate director in microbiology at AstraZeneca, working in the Global Product Development group. Sophie has worked in pharmaceutical microbiology for 10 years in both GMP quality control laboratories and pharmaceutical development. In her current role, alongside developing control strategies and regulatory steering, Sophie is focused on feasibility testing and the implementation of rapid technologies in the microbiology space. Sophie is also an active member of several industry consortiums involved in developing new technology solutions and in global pharmaceutical microbiological strategy.

Sophie Drinkwater is an associate director in microbiology at AstraZeneca, working in the Global Product Development group. Sophie has worked in pharmaceutical microbiology for 10 years in both GMP quality control laboratories and pharmaceutical development. In her current role, alongside developing control strategies and regulatory steering, Sophie is focused on feasibility testing and the implementation of rapid technologies in the microbiology space. Sophie is also an active member of several industry consortiums involved in developing new technology solutions and in global pharmaceutical microbiological strategy.