Microneedle Array Patches for Vaccine Delivery Clinical Evidence and Manufacturability

Reflecting on the feedback gathered from participants of the PDA Vaccines Interest Group (VIG) sessions, who identified innovation

in vaccines as a critical topic, a webinar was hosted on October 24, 2024, focusing on Microneedle Array Patches (MAPs), which offer an alternative in the field of vaccine delivery. This event saw the participation of representatives from both industry

and academia, providing an overview of the clinical evidence and manufacturability of MAPs and highlighting their potential to transform global vaccination strategies.

Reflecting on the feedback gathered from participants of the PDA Vaccines Interest Group (VIG) sessions, who identified innovation

in vaccines as a critical topic, a webinar was hosted on October 24, 2024, focusing on Microneedle Array Patches (MAPs), which offer an alternative in the field of vaccine delivery. This event saw the participation of representatives from both industry

and academia, providing an overview of the clinical evidence and manufacturability of MAPs and highlighting their potential to transform global vaccination strategies.

Technology Overview

MAPs include an array of tiny needles less than one millimeter in length and are designed to deliver vaccines intradermally, targeting the skin's rich network of antigen-presenting cells. This method promises improved immune responses, dose sparing and reduced need for cold chain logistics (1). The patches can be made from various materials, including silicon, metal, glass and various polymers such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid), polycarbonate and liquid crystal polymers. The MAPs also come in different forms, such as solid, coated, dissolvable and hollow microneedles.

Intradermal Delivery

Intradermal (ID) injection, traditionally performed using the Mantoux technique, involves inserting a needle at a shallow angle to deliver the vaccine just under the skin. Despite its potential advantages, such as improved immune response and lesser systemic reactogenicity (2), ID injection is not widely used due to the more complex injection technique and precise needle placement required to target the dermal tissue. MAPs aim to overcome these challenges by providing a more reliable and user-friendly method of ID delivery with microneedles and application systems that specifically target the dermis by design. By replacing the needle and syringe, MAPs also eliminate needle phobia and remove a significant barrier to treatment for some individuals.

User acceptance is crucial for the success of MAPs. Studies have shown that patients generally prefer microneedles over traditional injections due to reduced pain and fear (3). MAPs also offer the potential for self-administration, but there are potential user concerns about self-application and confirmation of the delivered dose.

Types of Microneedles

MAPs come in various forms, each with unique advantages and challenges:

- Solid Microneedles: These create micro-punctures in the skin, followed by applying a liquid, semi-solid or patch-containing vaccine. This form may allow using existing vaccine formulations, but dose control can be challenging.

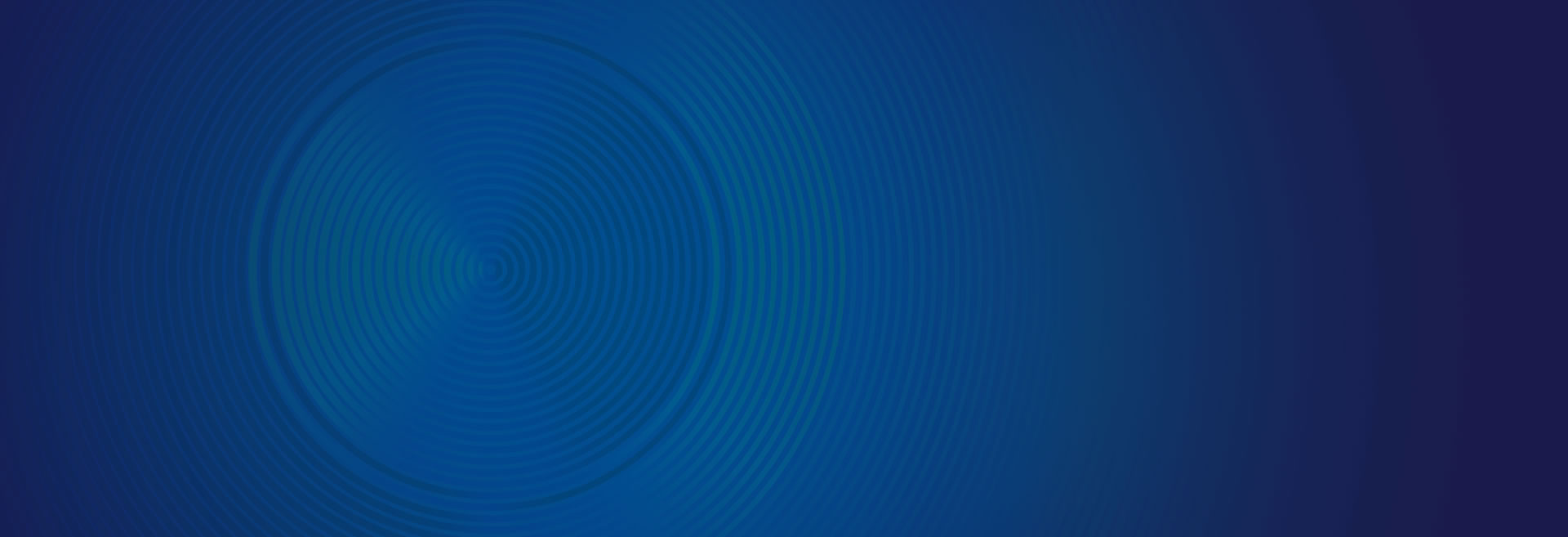

- Coated Microneedles: A vaccine formulation is coated onto the surface of the microneedles, which dissolves upon insertion into the skin. This method offers increased stability but requires precise control of the patch application process to ensure the entire coating is inserted within the skin where it can readily dissolve. (see Figure 1)

- Biodegradable Microneedles: These microneedles incorporate the vaccine directly within the microneedle. The microneedles dissolve or degrade following insertion into the skin, releasing the vaccine. They offer advantages in patch disposal but present challenges in manufacturing and require careful control of patch wear time.

- Hollow Microneedles: These are used to inject liquid vaccines directly into the dermis. They are commonly used in clinical trials but require high injection pressure and can be prone to leakage. They also do not address the stability and cold chain challenges inherent with some liquid vaccines.

Case Studies

The VIG webinar presented several case studies demonstrating the efficacy and safety of MAPs for delivery of vaccines and therapeutics. A few examples:

- Influenza and Rabies Vaccines: Reduced doses delivered intradermally via MAPs elicited immune responses comparable to standard doses administered intramuscularly (4, 5). This dose-sparing effect is particularly valuable during pandemics when vaccine supply may be limited.

- COVID-19 Vaccines: Studies showed that intradermal delivery of fractional doses of COVID-19 vaccines generated similar immune responses to full intramuscular doses, with lower systemic reactogenicity (6).

- Other Vaccines: Promising data were also presented for hepatitis B, inactivated poliovirus, yellow fever and hepatitis A vaccines, indicating the broad applicability of MAPs.

- Abaloparatide: A novel parathyroid hormone analog for the treatment of osteoporosis was developed in coated MAP form and evaluated in a Phase III clinical trial requiring daily self-administration for one year. The abaloparatide MAPs were well tolerated, provided consistent drug absorption and led to a therapeutically meaningful increase in bone mineral density following treatment (7).

Manufacturability and Scalability

The webinar also discussed the challenges and solutions involved in manufacturing MAPs at each stage of the development process, particularly at the commercial scale. Key challenges include:

- Material Selection and Fabrication: Different types of microneedles require specific materials and fabrication techniques, such as injection molding, photolithography and 3D printing.

- Drug Product Manufacturing: Each type of MAP requires a different set of manufacturing operations and process flow. Some of the operations are unique to MAP manufacturing and differ from standard pharmaceutical processes. As an example,

a high-level process flow for a coated MAP may consist of the following steps:

- Array Patch Assembly

- Sterilization

- Coating Solution Preparation

- MAP Coating/Drying/Packaging (in isolator)

- Secondary Packaging

- Equipment: There is no standardized MAP manufacturing equipment. Much of it requires design/build. An example was provided in which a custom isolator with robotic equipment for conveying MAPs through the coating and packaging steps was designed and built for commercial-scale production of solid-coated MAPs.

- Quality Control: Ensuring consistent needle dimensions, mechanical strength and drug content uniformity is critical. The development of standardized manufacturing processes and test methods is essential for large-scale production.

- Scale Up: Transitioning from lab-scale to commercial-scale production involves significant investment in tooling, automation and in-process testing.

Despite the challenges, developers are finding a path forward to commercially viable manufacturing processes. The MAP Regulatory Working Group, a collaboration between industry, academic labs, regulators and public health organizations, strives to expedite the path to clinical translation of MAP technology. One of their achievements to date is the publication of a proposed set of critical quality attributes (CQAs) to ensure the quality of MAP products. A few of the CQAs are listed below:

- Physical: Needle dimensions, mechanical strength and puncture performance

- Microbiological: Sterility and microbial limits

- Biological: Biocompatibility and immunogenicity

- Chemical: Drug content, excipient content and impurities

Manufacturing Case Study: Abaloparatide MAPs

A detailed case study on the manufacture of abaloparatide-coated MAPs highlighted the phase-appropriate scale-up of the process from lab scale through pilot and onto commercial scale:

- Pilot Scale Production: Abaloparatide MAPs were produced at a pilot scale to supply early clinical studies and the supplies to initiate the Phase III trial. The coating process was robust, with good uniformity and batch sizes of up to 15,000 low bioburden-coated arrays.

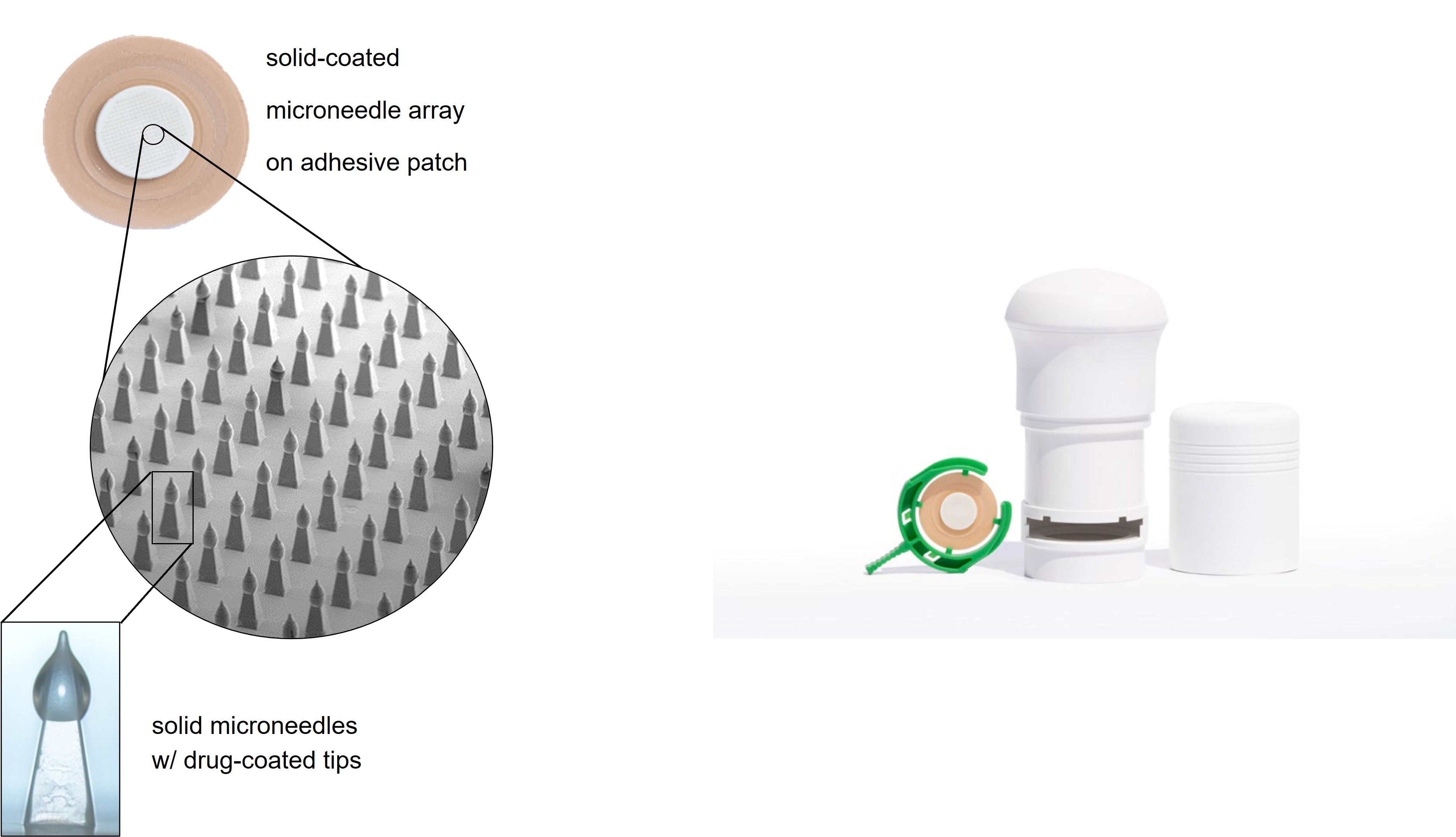

- Commercial Production: The process was transferred to the commercial site (see Figure 2), where the abaloparatide MAPs were produced with a sterile claim. A bioavailability study demonstrated the equivalence of the pilot and commercial processes. A total of over 200,000 abaloparatide-coated MAPs were produced for the Phase III clinical study, demonstrating excellent within-batch and batch-to-batch uniformity. A commercial scale line was designed and built with a capacity of approximately 14 million units per year.

Future Directions

The VIG webinar emphasized the potential of MAPs to enhance global vaccination efforts. Ongoing research and development are focused on improving the technology, addressing manufacturing challenges and expanding the range of vaccines that can be delivered using MAPs. Momentum is also building through increased investment from government agencies and non-governmental organizations specifically earmarked for the development of MAP products.

Conclusion

MAPs represent a valuable alternative in vaccine delivery technology, offering benefits such as dose sparing, improved immune responses and reduced cold chain requirements (1). Ongoing research and development efforts are paving the way for broader adoption of MAPs in both therapeutic and prophylactic applications. The insights shared at the VIG webinar underscore the potential of MAPs to enhance global vaccination efforts and improve public health outcomes.

References

- Chakraborty C, Bhattacharya M, Lee SS. Current Status of Microneedle Array Technology for Therapeutic Delivery: From Bench to Clinic. Mol Biotechnol. 2024 Dec;66(12):3415-3437. doi: 10.1007/s12033-023-00961-2. Epub 2023 Nov 21. PMID: 37987985.

- Niyomnaitham S, Atakulreka S, Wongprompitak P, Copeland KK, Toh ZQ, Licciardi PV, Srisutthisamphan K, Jansarikit L and Chokephaibulkit K (2023) Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of accelerated regimens of fractional intradermal COVID-19 vaccinations. Front. Immunol. 13:1080791. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1080791

- Birchall JC, Clemo R, Anstey A, John DN. Microneedles in clinical practice--an exploratory study into the opinions of healthcare professionals and the public. Pharm Res. 2011 Jan;28(1):95-106. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0101-2. Epub 2010 Mar 18. PMID: 20238152.

- Kommareddy S, Baudner BC, Bonificio A, Gallorini S, Palladino G, Determan AS, Dohmeier DM, Kroells KD, Sternjohn JR, Singh M, Dormitzer PR, Hansen KJ, O'Hagan DT. Influenza subunit vaccine coated microneedle patches elicit comparable immune responses to intramuscular injection in guinea pigs. Vaccine. 2013 Jul 25;31(34):3435-41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.050. Epub 2013 Feb 8. PMID: 23398932.

- Alberer M, Gnad-Vogt U, Hong HS, Mehr KT, Backert L, Finak G, Gottardo R, Bica MA, Garofano A, Koch SD, Fotin-Mleczek M, Hoerr I, Clemens R, von Sonnenburg F. Safety and immunogenicity of a mRNA rabies vaccine in healthy adults: an open-label, non-randomised, prospective, first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet. 2017 Sep 23;390(10101):1511-1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31665-3. Epub 2017 Jul 25. PMID: 28754494.

- Roozen GVT, Prins MLM, van Binnendijk R, den Hartog G, Kuiper VP, Prins C, Janse JJ, Kruithof AC, Feltkamp MCW, Kuijer M, Rosendaal FR, Roestenberg M, Visser LG, Roukens AHE. Safety and Immunogenicity of Intradermal Fractional Dose Administration of the mRNA-1273 Vaccine: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Ann Intern Med. 2022 Dec;175(12):1771-1774. doi: 10.7326/M22-2089. Epub 2022 Oct 25. PMID: 36279543; PMCID: PMC9593280.

- Lewiecki EM, Czerwinski E, Recknor C, Strzelecka A, Valenzuela G, Lawrence M, Silverman S, Cardona J, Nattrass SM, Binkley N, Annett M, Pearman L, Mitlak B. Efficacy and Safety of Transdermal Abaloparatide in Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis: A Randomized Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2023 Oct;38(10):1404-1414. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4877. Epub 2023 Jul 27. PMID: 37417725.