Flexibility—the Future of Manufacturing

As more pharmaceutical manufacturing moves toward individualized medicines, new solutions are being introduced that allow greater flexibility in both processes and facilities. These solutions also can enable the upgrade of aging facilities and the creation of smaller production footprints.

One concurrent session of the 2021 PDA Annual Meeting, “Flexible Facilities and Technologies: Innovative Options for the Future,” focused on the changes in blow-fill-seal technology, benefits of prefab cleanrooms, modernizing existing equipment, and how COVID-19 has affected operations.

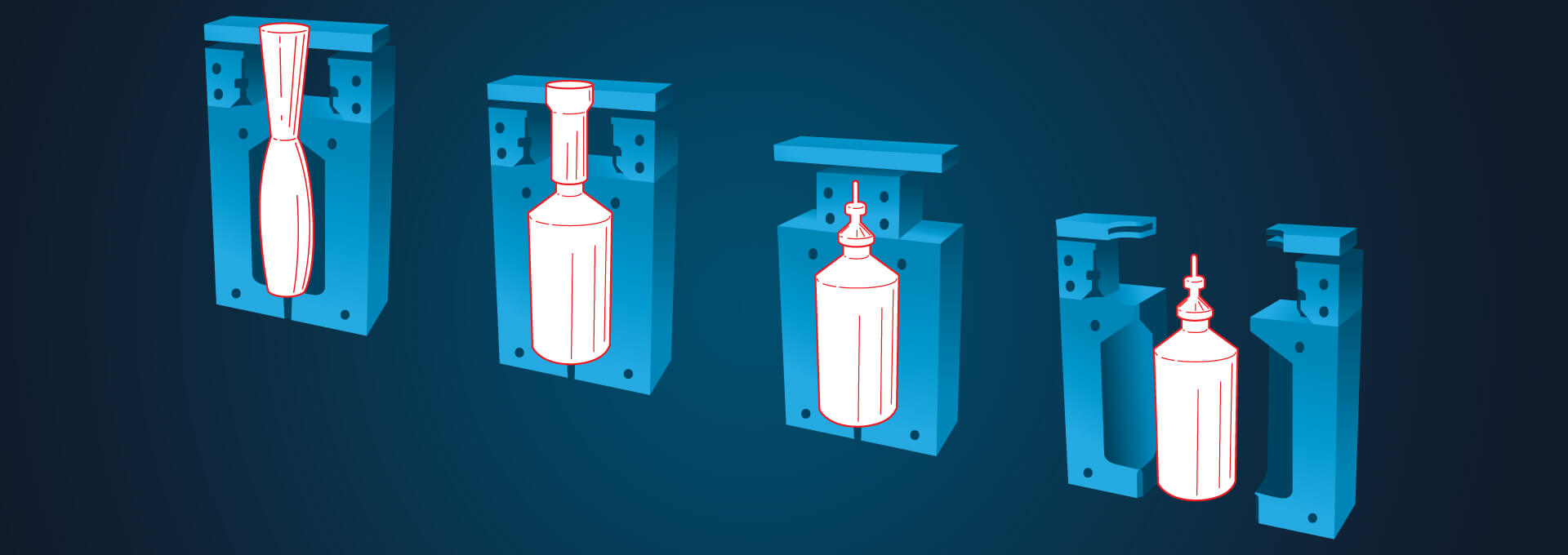

Leonard Pauzer, Director Process Technology, IPS-Integrated Project Services, provided an overview of blow-fill-seal (BFS) technology and explained how the method is becoming more prevalent in aseptic manufacturing, including filling vaccines. Technology has overcome a number of design challenges—integrating a needle with a BFS container in a closed parison, establishing a viral boundary and inactivating the vaccine within the filler, and controlling the product temperature.

IPS designs prefabricated cleanrooms, PODS, that are engineered off-site and then transported to and installed in a facility. And it requires careful, exacting planning. Because the weight and height of the BFS machine requires significant structural support, Pauzer said, on one job “once they locked down the location of the filler…essentially, the POD was built around it.”

According to Pauzer, one of the key reasons to move to the new BFS technology is the reduction in weight; the use of BFS single-dose plastic syringe barrels will reduce waste, save time over the traditional two-step process, and reduce the weight (and cost) of shipping containers. Another consideration, he said, was the flexibility to shape the container. “You can shape any container you want to meet the upstream needs without buying new machines … and that gives you options when you’re looking at delivery systems for patients.”

Another proponent of prefab alternatives, Peter Makowenskyj, Director of Sales Engineering, G-CON Manufacturing, talked about how modular and prefabricated cleanroom solutions benefit developers of new era of therapies. Current trends in global manufacturing—continuous manufacturing, rapid growth of ATMPs for individualized medicines, and aging of facilities among them—espouse the need for a smaller manufacturing footprint in order for manufacturing capacity to meet demands.

Makowenskyj compared the speed, flexibility, and costs of modular facilities to that of “brick and mortar, fixed-piping, sequential construction” facilities. Predesigned turnkey and box-in-a-box modules, he said, can be designed and qualified for any number of uses, including filling systems, cleanrooms, and mobile processing units that could be cloned at other locations or repurposed to manufacture different products.

“One of the main benefits is being able to operate concurrent streamlines when you’re designing and building these types of facilities. Another big facet is the level of quality you’re able to achieve by doing this in the Center of Excellence,” with the same skilled team producing critical elements—for instance, ISO 8 classifications require a specialized labor force—and using high-quality materials.

Thomas Busch, Project Director for Novo Nordisk A/S, described how his company modernized its existing facilities by introducing new innovative technologies and processes. First, Novo Nordisk evaluated how to make improvements that required downtime while still maintaining a sufficient supply of quality product to patients. Doing so in the GMP-regulated manufacturing environment, Busch said, required careful prioritization and planning. He presented two examples.

A cost-benefit analysis led the company to purchase new, off-the-shelf chromatography equipment that, using the existing footprint, reduced a bottleneck in the “capture” stage and required pre-approval for only the process change for new biologics manufacturing. Concept to implementation took 15 months and, with the new technology platform, also came the potential for other new uses.

Replacing open aseptic connections during filling set-up with a snap-in filler pump that could be autoclave-sterilized reduced the time and risk of batch change-overs. Proof-of-principle to pilot took 19 months. The new method also introduced a standardized means of setting up pumps and provided an innovative solution that will be rolled out to Novo Nordisk’s other sites.

In the process of moving to new technology, the company learned that moving a critical task required not only careful planning, but “thorough training for operators in all the tiny little details.” Busch also recommended “validating the equipment in the country of design, with all the experts in one place, before deploying it to the country of use.”

All three speakers agreed that introducing new technology requires a huge education process. While the people involved in making the decision to change a process or piece of equipment know why it’s an improvement, not every person in every level will understand it. So, it must be looked at it from a different perspective and advance a culture of information and training to ensure quality.

COVID-19’s Direct Effects on Pharma Manufacturing

COVID-19 having been “a big topic this past year,” session Moderator Kristen Dowling, Senior Manager, Quality for Amgen, asked each of the panelists: How has COVID-19 influenced existing and new projects over the year?

Makowenskyj: First, of course, we had to implement safe practices for our personnel and manufacturing sites. On a macro level, some schedules were impacted so we had to slow down a bit to match the on-site construction. And there was a huge demand for new capacity in building new sites to produce vaccines and using prefabs to mitigate risks. So now we’re catching up with the ‘normal projects’ that had been on hold.

Busch: Right away we had similar issues, dealing with all the unknowns—can we have on-site meetings with vendors? Can they come here? We put some orders in for off-the-shelf equipment and hoped to meet delivery times. Then we found we can do most of it virtually, which has mitigated project scheduling issues. But one area we saw some real impact is the single-use equipment, like connectors, bags, and tubing, because vendors had trouble manufacturing them during COVID.

Pauzer: One way for us was equipment testing for FATs. At first, going virtual was great! Then, when we could inspect the equipment on site, we noticed little things were missing, like insulation. We would have seen it in the field, but our emphasis was on ensuring the aseptic aspects, so we missed some of the low-level items. We’re not as sold on virtual FATs now as we were six months ago. We’re seeing there’s a lot of value in sending an employee to an FAT.

Pauzer’s last comment had all heads nodding in agreement: Resources, especially single-use, have had a major impact. If you’re not working on COVID or something related to COVID, you’re on a lower level in the distribution chain. Even with people—both companies we work with and in our own company—if you’re on a COVID project and juggling two things, COVID wins. Is your project on a normal timeline or a COVID timeline? COVID projects, timelines, and personnel trump all.